Posts Tagged ‘camel’

Livestock and landscapes

Posted in AFGHANISTAN, LIVESTOCK, PHOTOGRAPHY, tagged Afghanistan, camel, landscapes, livestock, photography, Sheep, shepherd on April 5, 2013| 2 Comments »

Nomadic livelihoods at stake in Rajasthan, India

Posted in DEVELOPMENT, LIVESTOCK, PHOTOGRAPHY, tagged camel, domestic animal diversity, Ellen geerlings, India, livelihoods, livestock, nomad, nomadic livelihoods, Raika, Rajasthan, Sheep, Thar desert, travel on May 2, 2011| 23 Comments »

The Raika represent one of the largest groups of livestock herders in India. Through their innovativeness, adaptability and specialised knowledge, they have managed to thrive in a harsh, semidesert environment. They have developed hardy livestock breeds and a complex social web that revolves around their animals. But external factors are pushing the Raika to the limits of their resourcefulness and threatening their livelihood with extinction.

The Raika or Rebari are one of the largest groups of livestock herders inhabiting the western districts of Rajasthan and Gujarat in India, including the great Thar Desert. Their population is estimated to be somewhere between one quarter and half a million people. The Raika were the traditional caretakers of the camel herds belonging to the Maharajahs. When the royal camel establishments were dissolved in the first half of the 20th century, many of the camels passed into ownership of the Raika, who switched to producing camels for the emerging market in draught animals.

Nowadays, camels are kept by a relatively small number of Raika families while sheep and goat husbandry is practiced by the vast majority to service a growing meat market. The Raika began keeping sheep about 200 to 250 years ago. During this time they have been influencing and developing the traits of their sheep by selective breeding and recently by crossbreeding with other breeds. In this way they have developed hardy breeds that are drought resistant, capable of walking long distances and able to produce lambs for slaughter.

Sheep husbandry and specifically breeding are generally regarded as men's domain, but it is really a system dependent on the labour of all members of the household. Often overlooked is the key role women play in terms of food production, maintaining agro-biodiversity, and providing labour. They also offer specialised knowledge in certain areas of animal husbandry and have specific decision-making roles.

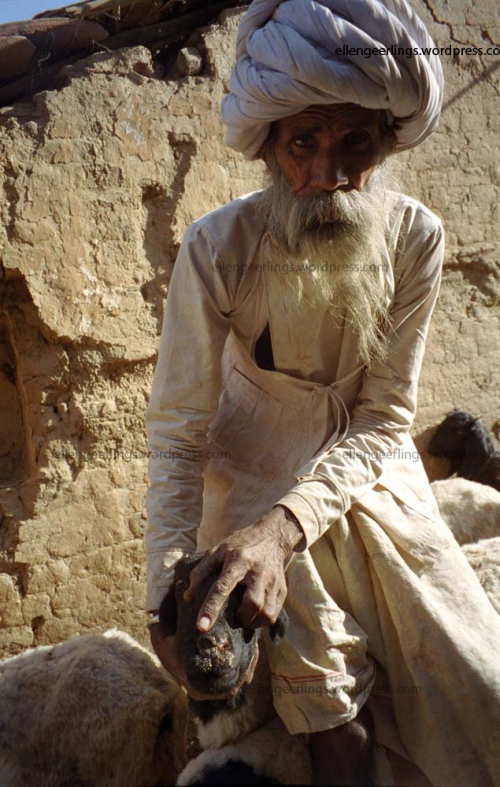

Due to the fact that they operate under migratory conditions, Raika pastoralists have traditionally resorted to self-treatment of their sheep and camel herds. Here a stone causing lameness is removed.

The Raika have developed their own system of animal healthcare making use of plant, animal and mineral based remedies, conventional drugs and traditional healers. Here a camel is fed plant-based medicines.

Every morning this Raika checks his sheep and goats before they are taken for grazing. Sick animals are left behind and taken care off by his wife and daughter.

Many of the Raika are able to distinguish between the different diseases, know the symptoms associated with the diseases and know whether diseases are contagious or not. This Raika is indicating a health problem in one of his sheep.

Treatments mostly consist of enhancing a sheep’s resistance by giving it edible oil mixed with turmeric or ghee or buttermilk mixed with turmeric (Curcuma longa) and jaggery. These mixtures contain high contents of proteins and energy and help the weakened sheep to regain strength and recover from disease. Additionally most respondents regularly visit a temple to pray for their sheep’s welfare and health. In some cases mantras are chanted for sick sheep and many sheds have small niches build in the walls in which small altars are build in order to pray for the sheep such as the one here.

Most households breed their own stud ram or rams, and the Raika follow a very careful selection process, which involves both men and women. They evaluate and inspect all close family members, especially the ram lamb's mother, using a system called nav guna, meaning "nine qualities". The mother of the ram lamb is assessed according to several criteria, the most important of which is milk production. The breed presented in this picture is especially favoured for its high milk production.

Sheep play an important role in social and cultural life. Before sheep shearing, the Raika perform a ceremony for Laxmi, goddess of money, who they hope will reward them with good wool prices and quality wool. They select some of their best sheep, rams and ewe lambs. These sheep are washed; paint (tika) is put on their head, and they are given jaggery and coconut while incense is burned. Some sheep are given silver jewellery to wear around their necks. When a lamb is born during the last day of Poonam (14th day of each Hindi month when it is full moon) or during Amawash (the 30th day of each Hindi month when there is no moon), the lamb is never sold or slaughtered. These Amar sheep (male) and Janri (female) give status and respect to the owner. The shepherd has offered the two sheep presented in the picture to a local Hindu deity. The Henna paint used during the ceremony can still be seen. Most Raika offer sheep to honour their gods or to ask the gods to protect their sheep. The sheep that have been dedicated to the deity are considered sacred and can no longer be slaughtered or sold by the shepherd.

Raika herds are passed down from father to son. Many generations of Raika took pride in their occupation and were able to make a good living out of sheep and goat husbandry.

Young Raika men are not as keen as their forefathers to take up pastoralism. Despite a growing demand for animal products such as meat and ghee, there are several factors that challenge the pastoralist lifestyle. Solutions seem to lie increasingly beyond the reach of the Raika, entangled in a complex mix of local politics, unfavourable national agricultural policies and conflicting interests within the Raika themselves. Several recent developments, including long drought periods in the last ten years, overpopulation, increasing disease pressure and decrease in fodder resources. Migration is increasingly getting more difficult because irrigated fields get in the way of migration routes and do not allow sheep to graze on the stubble. The Raika unanimously cite the shortage of grazing land as a serious threat to their livelihood. This herd has to travel greater distances each year to find grazing grounds.

In addition, Raika society is inherently conservative; it is ruled by elders who are sceptical about change and do not realise the need to adapt to new circumstances and adopt new skills. These elder Raika do not necessarily share or defend the interests of younger Raika pastoralists.

These are but a few of the forces that have been changing the ecological and institutional landscape in Rajasthan. The Raika have not been favoured by any of these changes and are increasingly marginalised. When the Raika are forced to sell their animals there are few alternatives but to take up low paid labour in cities that are already overpopulated. This leads to disrupted families, frustration, alienation and sometimes alcohol abuse and HIV infection. Raika identity is tied to their animals. This distinguishes them from others and gives people a sense of pride, independence and well-being. If the Raika lose their livelihood, valuable breeds and invaluable knowledge will also be lost.

This young Raika boy is doing his homework early in the morning before going to school while his mother is preparing breakfast. His father has gone on migration and it will take months before he will be back. Whether this boy will be able to continue his father’s profession remains uncertain.

This blog was reproduced from a feature I have written for Seedling magazine with a few changes and additions.

This feature was edited and published in New Agriculturist

Sources I used for this blog:

Geerlings, Ellen. (2004) The black sheep of Rajasthan. Seedling magazine, October issue p.11-16. Genetic Resources Action International. Barcelona, Spain.

Köhler-Rollefson, Ilse. (1999) From royal camel tenders to dairymen: occupational changes within the Raikas. In Eds. H Rakish and J Rajendra: Desert, Drought and Development: Studies in resource management and sustainability, Institute of Rajasthan Studies, Jaipur.

Acknowledgements

I’d like to thank the Raika who provided me with their valuable information and time, the League for Pastoral Peoples for their support and giving me the opportunity to work with the Raika, Lokhit Pashu Palak Sansthan for logistical help and support, and especially to Ramesh Bhatnagar for his help, patience, translation and good company.

More information on the Raika can be found at:

http://www.pastoralpeoples.org/

All the photos posted on my blog are owned by me and they should not be used without my permission